At the Garrmalang Elders event in Darwin, it became clear that storytelling isn't just about the past; it's about keeping culture alive today.

Elders like Uncle Roque Lee, Aunty Adela Graetz (née Cardona), and Charlie King reminded me that every story shared is a thread connecting generations. Their words carried humour, heartache, and deep cultural pride, offering lessons you won't find in books. When they spoke, they offered the audience a map; one built on lived experience, love, and survival. Stories like theirs ground us. They remind us who we are, where we come from, and how we walk forward.

The first to speak, Uncle Roque.

"We still remember who we are," he began. He told us about steering airboats across swollen rivers, stopping mid-patrol to sit with old painters and "steal" their colour secrets, and coaxing young rangers to carve their first spear.

Every anecdote carried a heartbeat of humour—he is a natural stand-up—but beneath the laughter lay a stubborn truth: culture is work. "I'm still making spears the way the old fellas taught me," Uncle Roque said, holding an invisible lance between calloused hands. "Now my nephews copy me. That's the fire still burning."

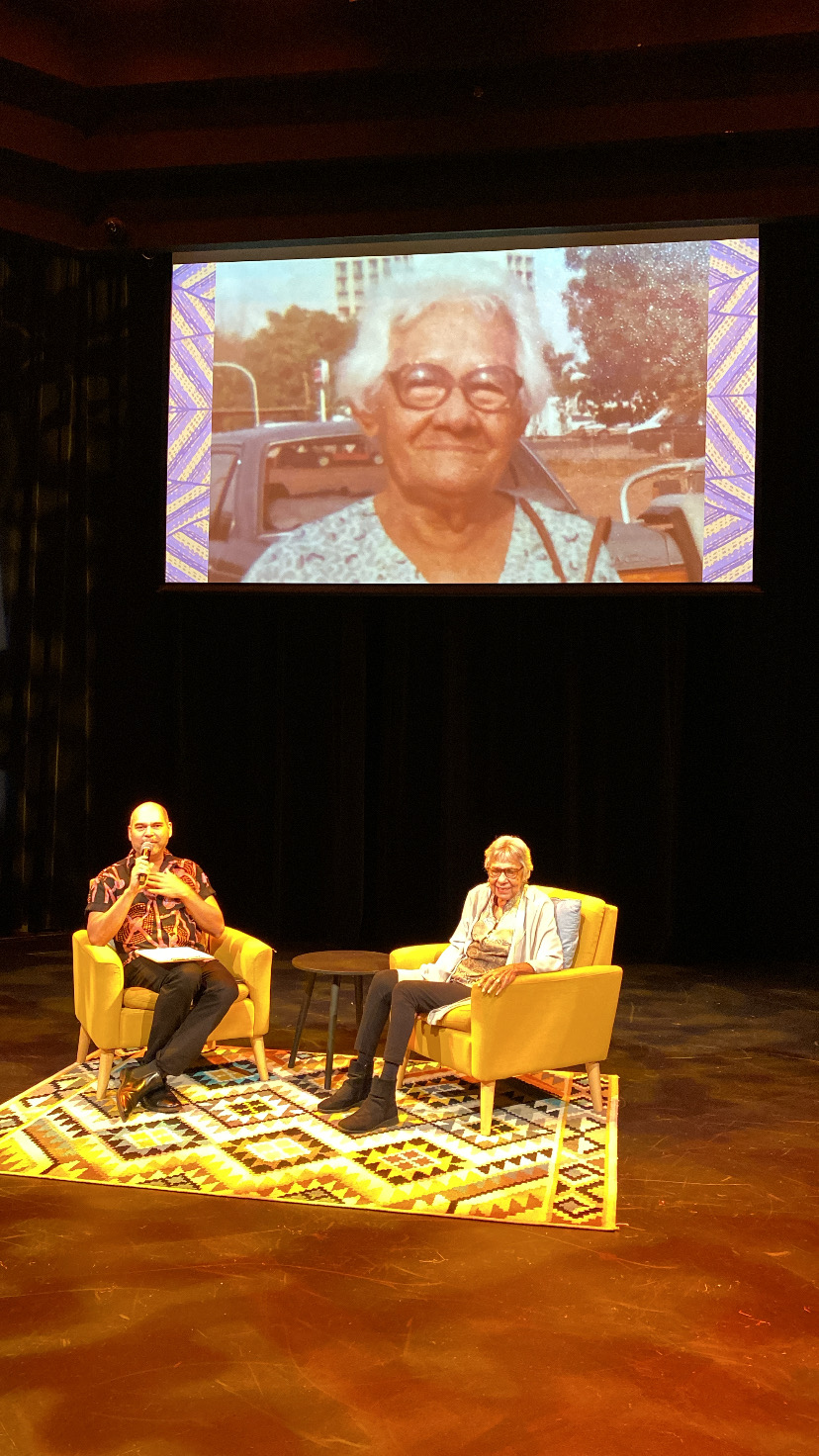

Next up, Aunty Adela and the tempo gentled. Her memories rolled out like a lullaby over tin roofs. She painted Edwards Street in the 1960s: every veranda sagging with cousins, guitars tuned to Territory humidity, and aunties dancing barefoot until Cyclone Tracy claimed the power. Aunty Adela's eyes shone when she spoke of her father, wharfie and Rondalla Band guitarist Peter Cardona, who mended throw-nets by lamplight and brewed coconut oil from backyard palms. When tuberculosis took him at fifty, it was matriarch Nana Sal — a Badu Island woman with lightning in her spine — who marshalled nine children and half the neighbourhood into order.

"She ruled like the military," Adela laughed, voice tight with love. At eighteen she married Trevor Graetz, "the only boy at Darwin High with a car," and fifty-four years on they are still each other's favourite duet. Her story was a hymn to kinship: when one string snaps, the song survives on the others.

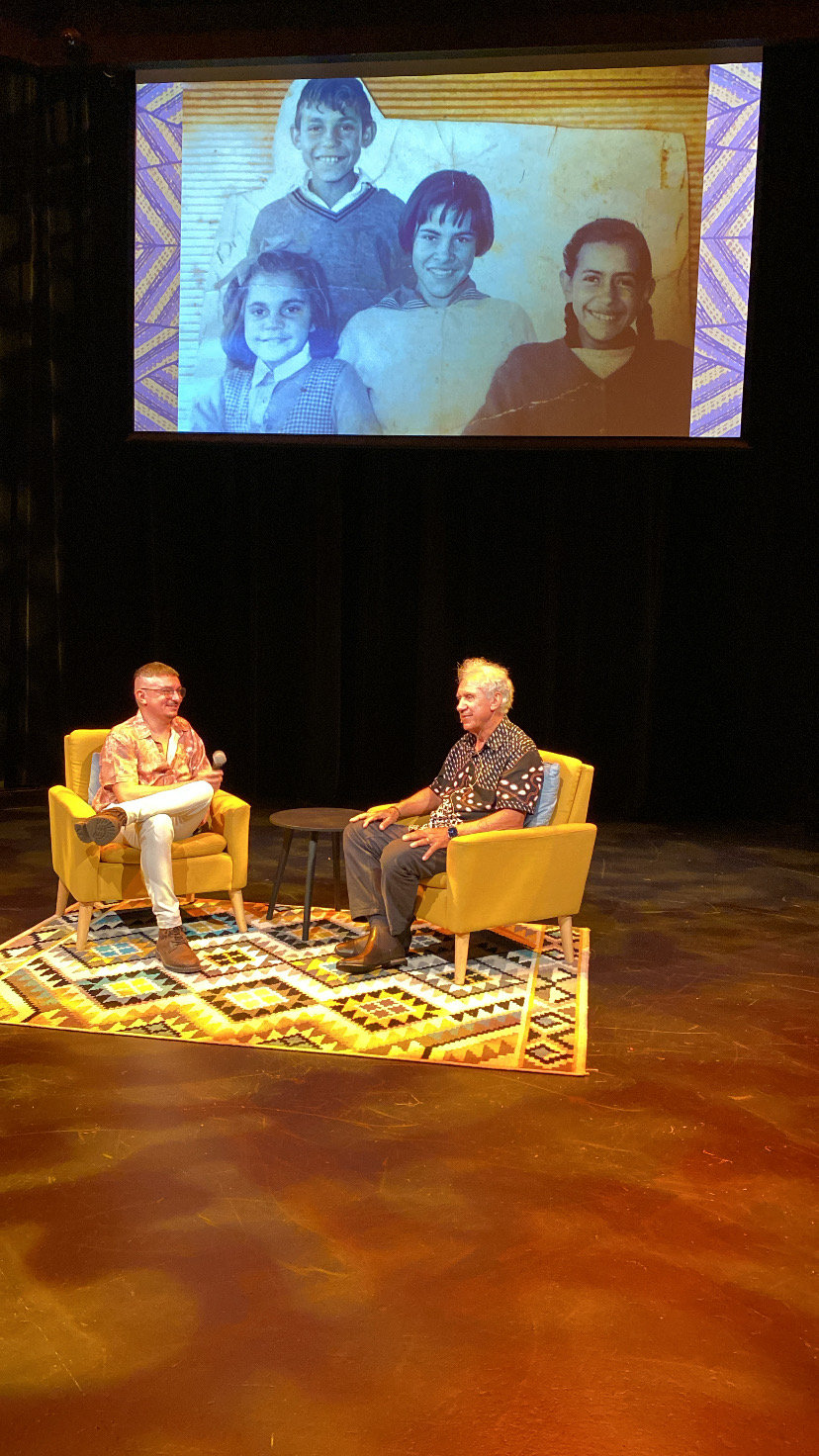

Finally, Charlie King stepped forward, and the night hushed as if an old radio set had crackled back to life.

"I'm Gurindji," he said softly, "tribal first, always." He traced his mother Ruby's stolen-generation journey; taken from Gurindji Country at age eight, terrified by her first sight of the ocean, and locked inside Darwin's Kahlin compound. Later, she found unexpected love while working at the hospital. Jack King, sun-struck after cycling 3,500 kilometres from Melbourne, opened his eyes to see Ruby sweeping the floor. "He thought he'd died and gone to heaven," Charlie smiled.

But the most powerful moment came when Charlie recalled a night that lives in the memory of millions: the death of Princess Diana. He was in master control at the ABC, his friend Wayne Shields on air, when the news came in via the BBC.

"I ran in and told him — she was gone," Charlie said, pausing just long enough for the weight of that moment to land. "That's the responsibility we carry in radio; to share the truth with the world, no matter how hard."

It was a striking reminder that our storytellers aren't just holders of culture — they're witnesses to history.

Charlie's voice trembled again when he spoke of sitting at his father's feet, listening to boxing broadcasts, unaware that one day he would call Olympic bouts himself.

"We were poor," he said. "But Mum stitched wogga-rug blankets from scraps, and that kept the cold — and the world's judgment — off us." In his rhythm, you could hear both a commentator's cadence and a son's quiet pride.

As the applause faded, I realised every sentence tonight painted a picture on a map. Uncle Roque showed us culture as obligation. Aunty Adela revealed family as orchestra. And Charlie reminded us that identity travels — sometimes by bicycle, sometimes by broadcast — but always lands in the heart.

We often say Elders are living libraries; after tonight I know they are also campfires; places we gather to warm ourselves, cook new ideas, and remember the taste of old ones. My job as a storyteller is to carry their embers carefully onto this page. Yours is to keep the flame alive.